Ö5 Artist: Erik Thörnqvist

Interviewed by Yuän (ÖÖÖ)

#

ÖÖÖ:

Through “Re-working The Victory Over the Sun”, you characterize the sun as “an agent that acts upon the same plane and in conjunction and contention with humanity”. In the introduction of this work, there are radical changes and stages referred to the roles of the sun in human history. From a divine omnipresence that had been worshiped, to a ruled and harnessed provider. Collective humanity experienced its anthropocentric and egocentric periods along with modernism progress. And then, how does the sun shift to such a current situation in your artwork?

Solo show at Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, US. Curated by Ben Sang

Photo by Hudson Kendall & Ben Sang. Courtesy of the artist & Final Hot Desert

Erik Thörnqvist:

To address that exact question, my proposal was to shift the original story’s narrative. The people of the future rebel against the sun and lock it away in a concrete prison in the first Cubo-Futurist opera, ‘Victory over the Sun,’ which had its world premiere at Luna Park in St. Petersburg in 1913. I wonder if the keys to the concept of nature vanished when the Russian avant-garde locked the sun and threw away the keys in a total revolt against the Romantics. In my work, presented by Final Hot Desert on the Bonneville Salt Flats, I sought to stage a scene in which the sun had instead been released from its prison into the 21th century. How might the sun now interfere and engage with its environment after a hundred years? Given that there is no physical adversary or audience, we as viewers become the counterpart that is addressed.

#

ÖÖÖ:

You created “Re-working The Victory Over the Sun” in 2022, the era of several global crises we are dealing with pandemics, climate change, and so forth. What is your insight about the next collective state between nature and humans in the future?

Erik Thörnqvist:

As you say, we appear to be in a perpetual crisis, almost like a big crash in which every aspect is accelerating. At the same time, I have the impression that the crash is a frozen state where everything falls so slowly, almost as if it is fixed. If a crash is a structural change in which the system itself (economy, politics, production relations) is in crisis, in which the productive forces are no longer in line with the needs of society, then the crisis is also structural and cyclical: each acceleration affects all of them (i.e., capitalism is in a structural crisis) and each reform leads to another crisis. On the one hand, I believe we must constantly scrutinize the legislative frameworks that enable crises, and on the other hand, as artists we must present the alternate utopia we need to see.

#

ÖÖÖ:

What did you experience through the preparation journey of your solo exhibition in the natural landscape with Final Hot Desert?

Solo show at Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, US. Curated by Ben Sang

Photo by Hudson Kendall & Ben Sang. Courtesy of the artist & Final Hot Desert

Erik Thörnqvist:

When Ben Sang, the founder of Final Hot Desert, first contacted me over three years ago, inviting me to do a solo show, I was ecstatic and immediately began planning. I proposed a larger idea that required more time and resources, and we were able to obtain funding from The Swedish Arts Grant Committee – which made the whole project possible. We scheduled the show for March 2020, but unfortunately had to postpone it three times due to the pandemic. It wasn’t until the US finally gave the go-ahead for Schengen countries to re-enter the country that we were ready to set a new date for the show in spring 2022.

Me and my boyfriend landed in Salt Lake City, shaken up after a long haul flight and a rather complicated logistical problem trying to get five checked in suitcases filled with art into the country. Ben picked us up in a huge SUV at the airport and drove us to our hotel, Little America, where we literally collapsed from fatigue. The next day was scheduled for us to be just jet lagged and stay in a much needed horizontal position. On the day of the installation, we drove three hours west to the Nevada state line before arriving at the Bonneville Salt Flats. A 19 kilometers long salt flat with a 1.5-meter-deep crust in the center. We drove out for a long time on the perfectly leveled salt. Because of the previous day’s rain and the way the wind was blowing, the surface water formed an unusual mirror-like thin layer that was breathtakingly beautiful. Stepping out of the car onto the salt flat is one of the most unworldly sensations I’ve experienced. The salt looked similar to a gigantic frozen lake, mirroring all light as well as the surrounding landscape. The astounding contrast between the ultra flat salt and the scenic mountain range surrounding it is difficult to put into words. Almost as if it was possible to see the land curve towards the horizon.

#

ÖÖÖ:

In “Big Science, Small Country”, you brought a gaze from your grandfather who had been part of constructing the escape road part of the Esrange Space Center in the 1960s. It was an infrastructural project implicated both in the arms race of the Cold War, and in the wider project of earthly as well as planetary expansion. What path of the story is there when the line for time has been obscured? How are macroscopic and microscopic sensibilities affected by each other and integrated into the one narrative?

Photo by Thomas Hämén. Courtesy of the artist and Norrbottens Museum, Luleå

Erik Thörnqvist:

In the post-war period, space programmes became a key element in the effort to construct a notion of state sovereignty. The North was seen as somehow similar to space because it was “so far away”. It was seen as a territory that had not been exploited or inhabited and thus possessed the raw power of nature. In the 1950s it was even called “the nordic room” in the sense of a resource, and it was considered safe to launch rockets there. But of course people lived there. The development of civilian and military technology is seen as going hand in hand, so a rocket is both science and threat. The term ‘big science’ is used to describe large projects where several European countries joined forces to gain greater influence in the power struggle and competition with the Soviet Union or the United States. So this space station was built with funding from ESA (European Space Association), whose headquarters are in Paris – it wasn’t just a project run by the small country of Sweden.

I happen to have a personal connection to the area – through my grandfather, who built the escape route where the rockets would fall down. In this building project he acted as a colonizer, as he acted as a representative of the nation state. The underlying idea of ‘Big Science, Small Country’ is to connect the space industry, the mining industry, local stories and my personal story. It focuses on power structures, voices, and different desires existing in the northern part of Sweden, such as the desire for wealth and the desire to claim the land itself. The road then becomes a projection surface for how history should be presented and who is entitled to it. When someone introduces fiction among a representation of reality, I believe it creates an opportunity to convey a new meaning in this reality. The para-fiction becomes either so real or so clear that we can unsettle the boundary between reality and art, and instead create a different narrative. The road serves an infrastructural function by helping the Sami to get to their herds more easily, but it also facilitates the space station’s exploitation of the untouched land. By building a new road, the colonizer can travel to “new” lands and rename them.

For me, it is impossible to represent this exact reality because representation is a violent act in which power is exercised and judgements are made, which means that only part of the story becomes visible. I wanted to create a work that speculates on these different states of reality-making. Hence Big Science, Small Country is itself ambivalent and dreamlike, with trans-like music reminiscent of a sci-fi film.

#

ÖÖÖ:

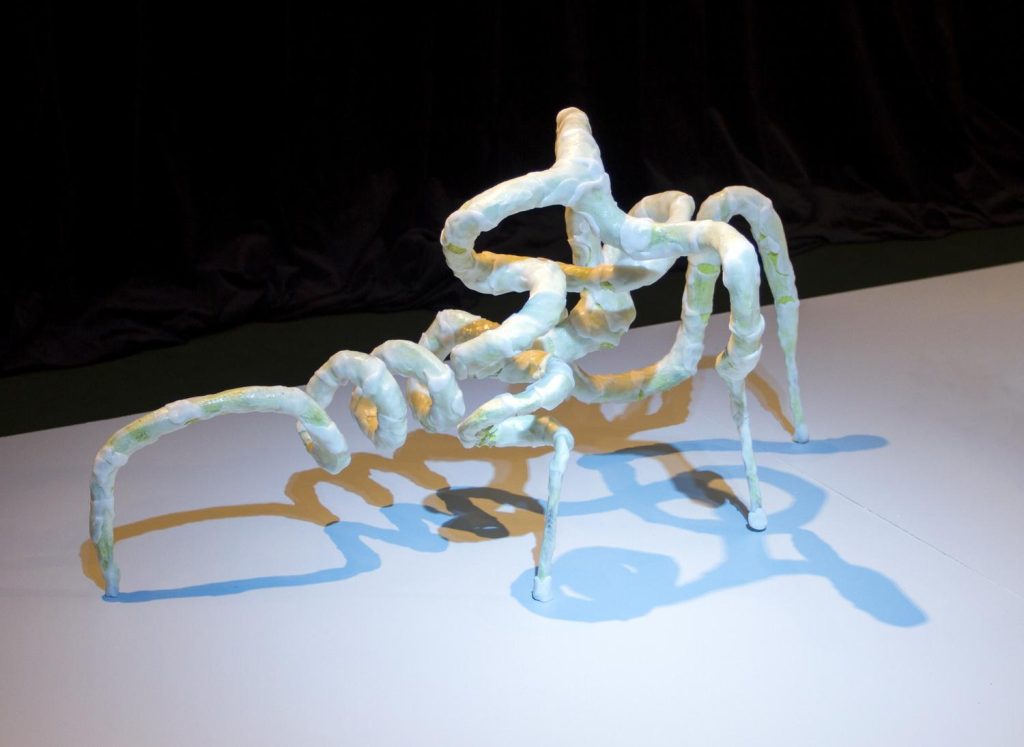

And the sculpture “Cartesian Crawler” is based on the same geographic reference as “Crash-zone B” of Esrange in the last installation we discussed. It is a mutated phantom from numerical coordinates of political issue-related data. And seems born of both utopia and dystopia. What is this fabulous creature symbolized for? Which direction is it crawling to?

(from left to right, top to bottom) Artworks in image 1,2 exhibited at duo show ‘Flight of Doves'(2021), 3,4,5 exhibited at ‘Luleå Biennial'(2020)

3,4,5 photos by Thomas Hämén. Courtesy of the artist, Konstnärshuset Stockholm and Kulturens hus Luleå

Erik Thörnqvist:

The Cartesian Crawler has the same diameter – 1.5 meters – as 21 small shelters built in Crash Zone B, close to the road. These tubes would shelter the local population if a rocket fell. Warnings would be broadcast over the radio, and then they would flee to these shelters – hollow pieces of infrastructure. It also happens to have the same diameter as the largest rocket that took off from the launch center. So for me it became very important to use scaffolding to draw attention to the fact that infrastructure can be seen as ideology – because it’s a hollow form in one way, and useful in another. The rocket, the science and economics around it becomes the proof of how developed we are, but for the people who live in the area the rocket becomes a dangerous threat. The Cartesian Crawler then becomes a ghost, an unknown being to humans, another projection of something that is not me and that can travel along these desire lines to haunt us, or to act as a guardian, a skeleton, a remnant of whatever the desire is directed at.

#

ÖÖÖ:

Your oeuvre forms affective states crossing over time and spatial dimensions. Based on historic, collective and personal references, each certain angle is located with quasi-scientific facts yet brings over different fictional and experiential universes. How do you start and specify perceptive angles on your story coordinates? Are they developed from a hypothesis or established reflection that you are exploring?

Part of the group show Uttran II in the south of Stockholm. Photo by Andreas Tang

Courtesy of the artist, Tora Schultz Larsen, Maiken Buus Andersen, Christian Aagaard Ovesen and Emilie Palmelund

Erik Thörnqvist:

It undoubtedly tends to vary in each proposal; it might start out of a past memory, an archival artifact or a hazy picture. I do think it starts first with my conviction in the potential for seemingly unrelated references to sync. Constructing those seemingly conflicting links possesses a potential, made possible within an artistic practice. I think there lies a capacity of the art object it retains in regards to how we might renegotiate agency and testimonies within that discourse – unlike the medial or juridical sphere. New sense-making dialogues for decoding can emerge in these transfers and joints; between analogue and digital, prefabricated and found. Between these gaps and wedges, like the soft bends to which steel can be formed, the moment when a 3D file takes a material state or the softness of fur that yet contains a ferocious side. In that space of mediation, the gaps and wedges have an ability to reveal other narratives.

#

ÖÖÖ:

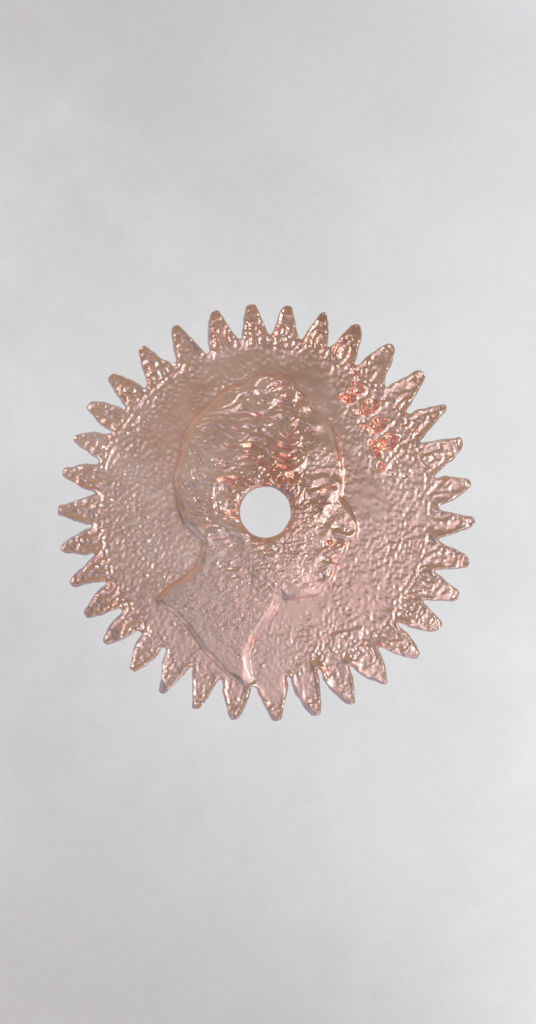

Cogwheel is another common object threading through many of your works. The essence of a cogwheel is an object that transmits or receives motion by wheel mesh with another wheel. It can be a letter of gear, force, labor, system and corporation. Do the cogwheels have fluid meanings in your different artworks or do they direct to a certain implication?

Middle: The 1700 century coin that Erik found in Norrbotten’s County Archive

Courtesy of the artist, Royal Institute of Art and Marabouparken, Sundbyberg, Stockholm

Erik Thörnqvist:

My obsession with the cogwheel as a symbol started when I found a coin in Norrbotten’s County Archive, a 1700 century shilling that was turned into a cogwheel. Someone had at some point sawn out 34 cogs and drilled a five millimeter hole centered in the coin. What used to have the ability to figure in the world as currency and means of payment. What once paid for bread now appears in a different system – as part of a machine system. At the same time, to me, it looked like the iteration of a stylized sun symbol or a flower. Those translations and the ambiguity that appeared felt fascinating, and later trying to capture that in-between state I experienced.

#

ÖÖÖ:

How do you perceive the interweaved reality between our ongoing life and imagined science fiction?

Part of the group show Uttran in the south of Stockholm.

Courtesy of the artist, Tora Schultz Larsen, Maiken Buus Andersen, Christian Aagaard Ovesen and Emilie Palmelund

Erik Thörnqvist:

Like a possibility to escape and dream of something else.

#

ÖÖÖ:

By the end of the interview, could you please share any music, film, or book that you like recently?

Thank you so much for taking the time to share your insights with us.

Erik Thörnqvist:

Nausicaa valley of the wind – Hayao Miyazaki. Studio Ghibli

Artist Info

Erik Thörnqvist

ig – @seasonal_fruit_cake

Evoking the rawest creativity in human nature, ÖÖÖ is growing in primitive future.