Ö9 Artist: Justin Fitzpatrick

Interviewed by Yuän (ÖÖÖ)

#

ÖÖÖ:

In your painting series, all kinds of rational reality are woven with phantasmagoria, where the mind’s world is diagrammed with the impacts of desire or emotion. Indicating that cells of matter correspond to particles of thought, creating a constant, cyclical movement that dissolves the boundary between the self and the world. What does this dissolution of boundaries signify?

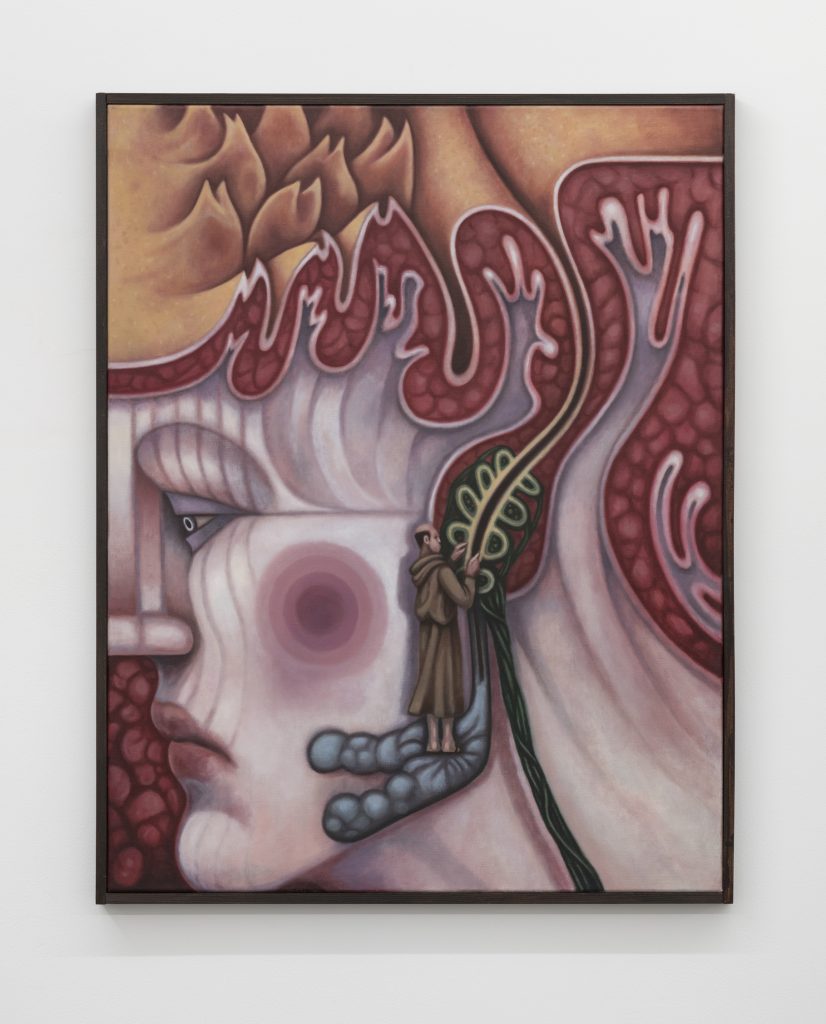

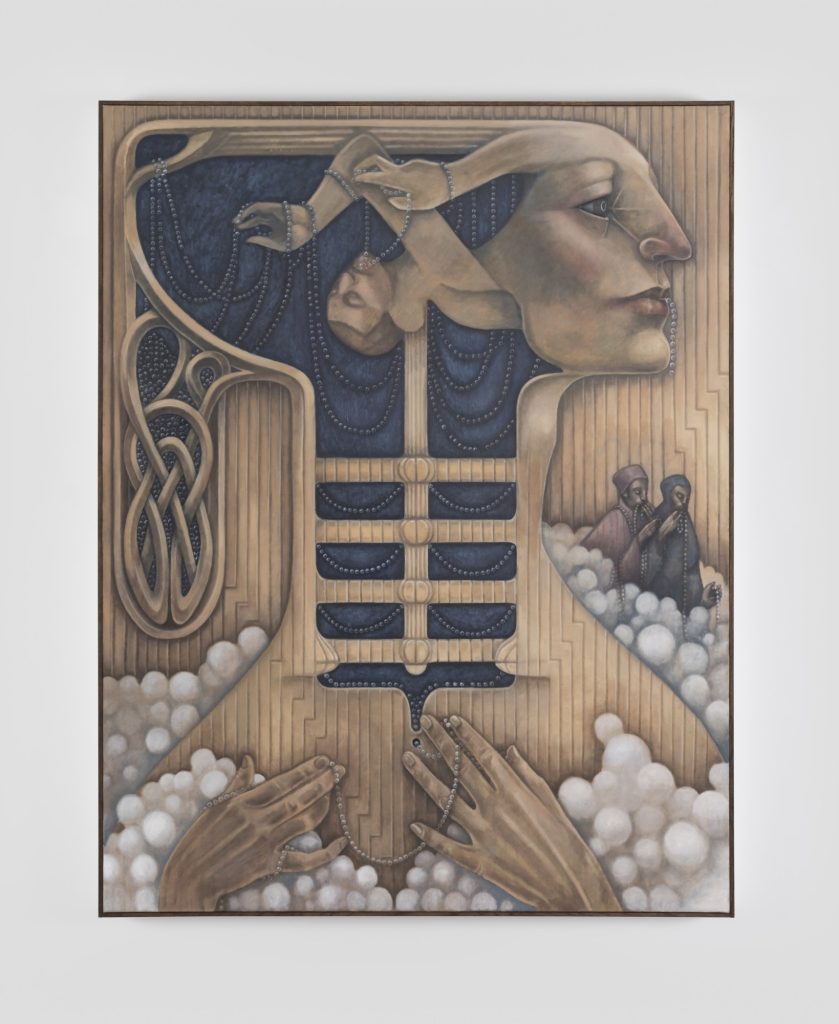

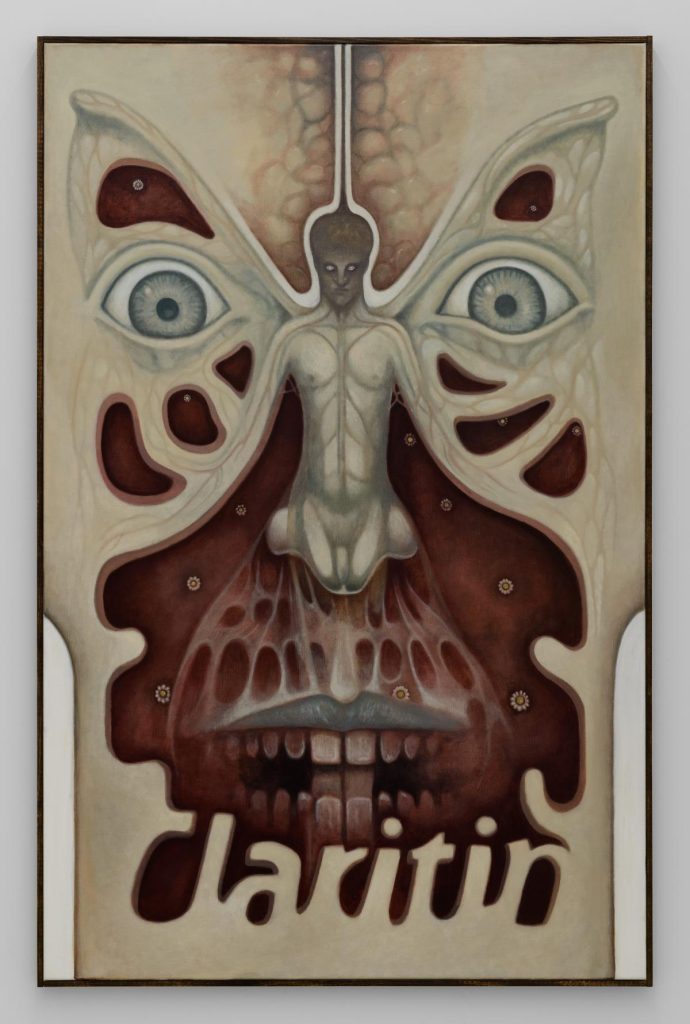

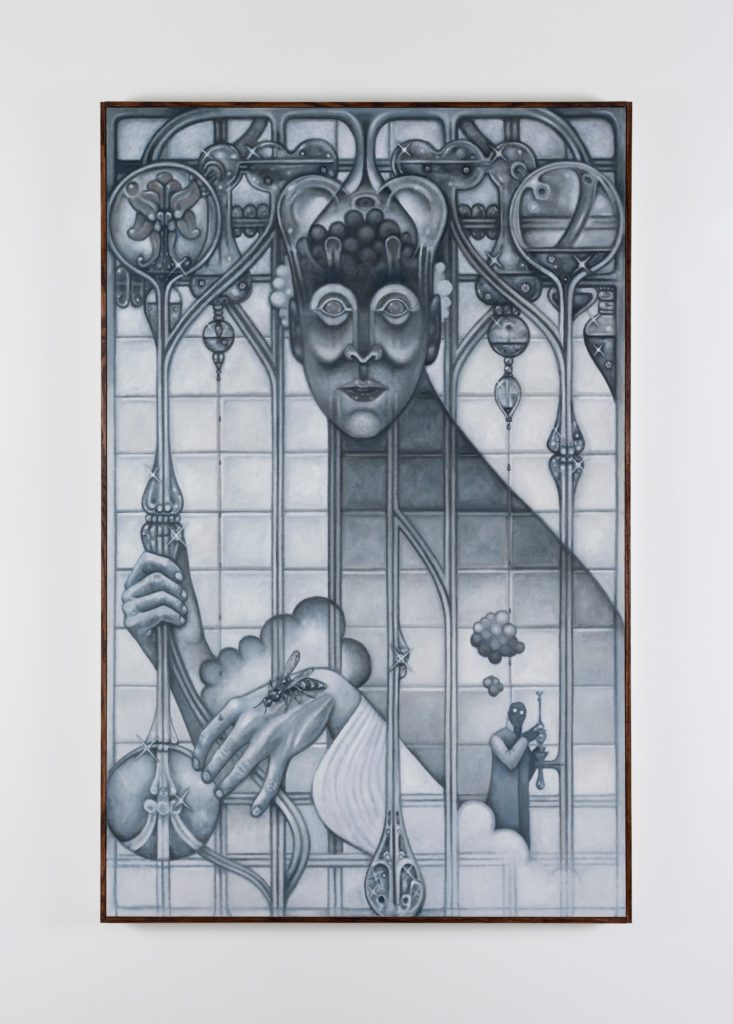

Middle: Hormones and Memory,2022

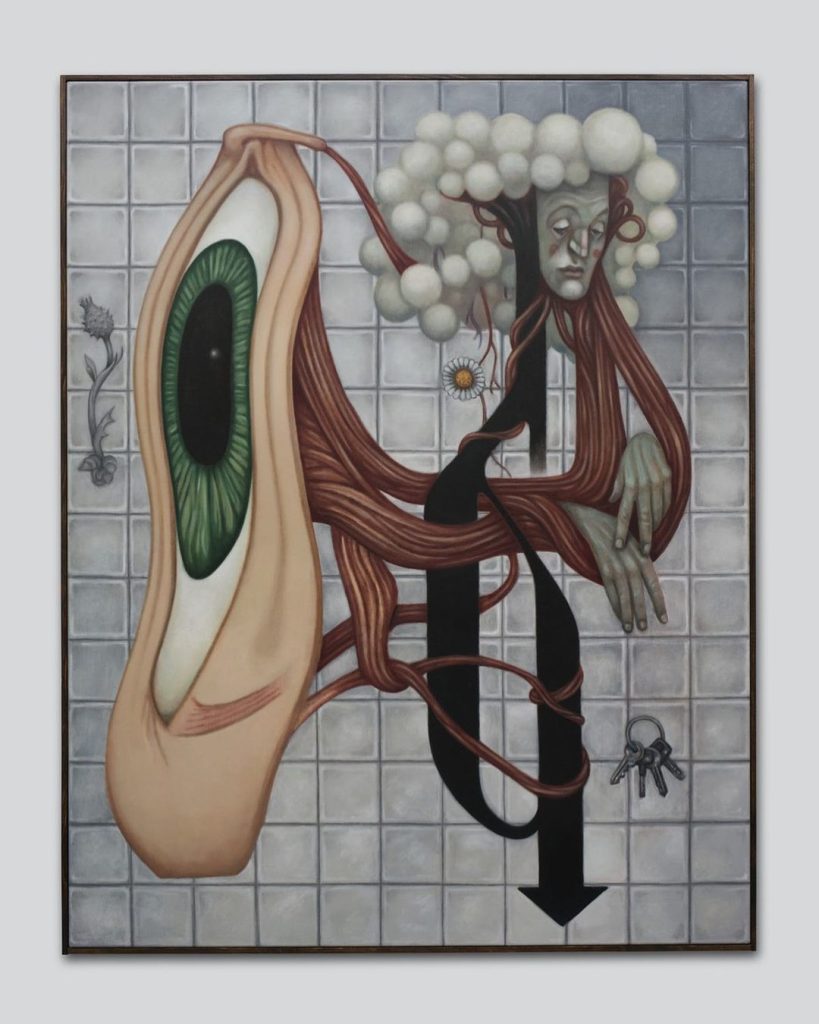

Right: A Drunk Man Looks At A Thistle ( While Dropping His House Keys),2022

Photography by Damien Griffiths. Courtesy of the artist and Seventeen, London

Justin Fitzpatrick:

When you start to think about your physical composition as a collection of millions of cells, the perceived unity of the body dissolves into a multiplicity. I think of this multiplicity in regards to agency. When i interrogate my own agency I am often unable to account for a lot of my motivation. I can’t get a handle on who this agent is. In the studio i am constantly demanding of myself ‘ why am i doing this instead of doing that’ and i suppose the questioning becomes a natural subject matter to pursue, so i started to look at it from the philosophical but also the biological level.

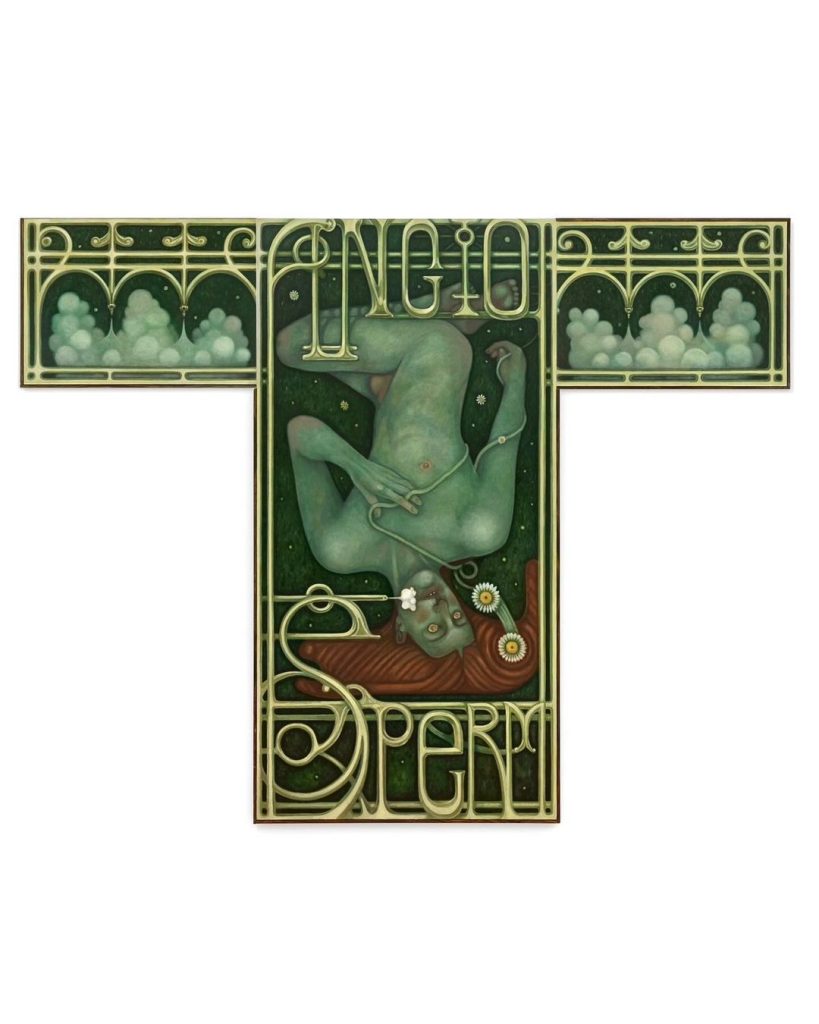

On the level of consciousness a total dissolution of boundaries between the self and the world (however one induces it) could be an ecstatic event but could also be a psychotic break. In some recent work, specifically the Angiosperm Telephone show, i focus on these ruptures of the self, where the individual (in this case a priest) is invaded by something external (the smell of a perfume): a libidinal event that destabilises them totally. I often use religious figures because they represent a rejection of the physical world in order to better attune themselves to the world of the spirit. But this transcendence alienates themselves from themselves and so i am often depicting these ‘ecstatic’ events, where the physicality of the body and the structures of selfhood are brought back into relation, usually depicted as a kind of gothic horror.

#

ÖÖÖ:

During this state of dissolution and merging, there is often a cyclical system composed of transformed bodies that create either a passage or a space. What does this system define? After dissolving the boundary between inner and outer, do these selves still serve the integrity of their sensibility, personality, and identity, or do they take on a new form of existence?

Justin Fitzpatrick:

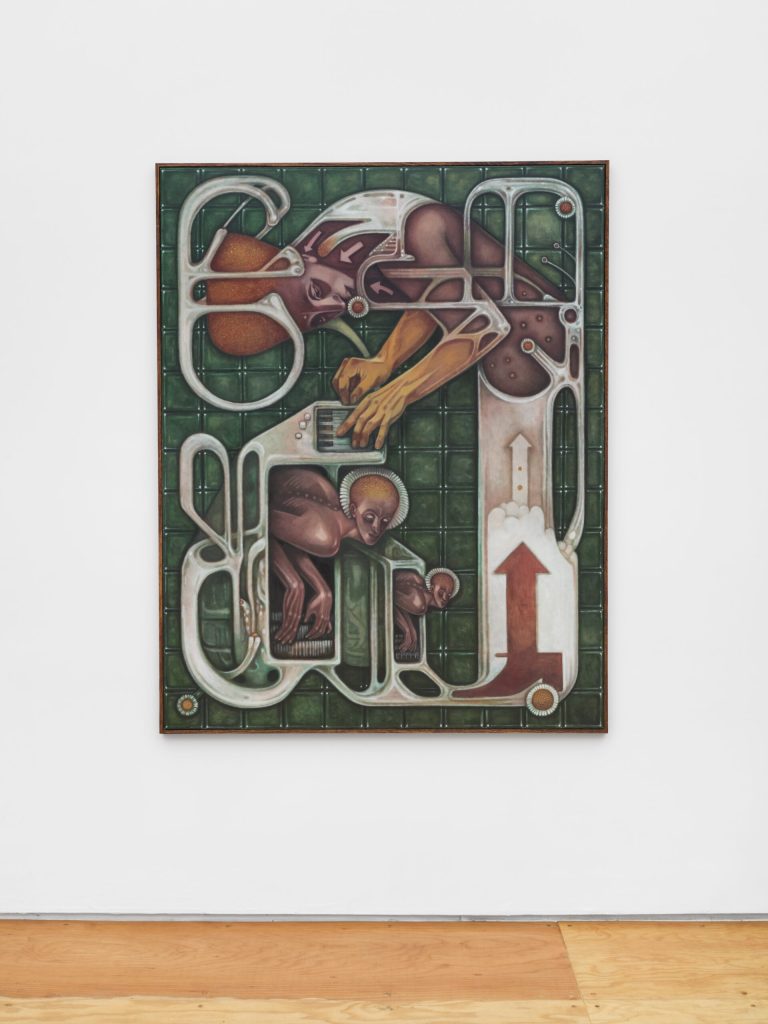

In some of my paintings, the interiority of an individual is described as a landscape or an architecture and characters inside represent the affects that drive the individual to action. For me the pleasure in making works like this is trying to make visual these psychological structures, to make paintings that can be at the same time diagrammatic and also hopefully affective. With these kinds of ‘body as architecture’ paintings, the beings depicted don’t really have an integrity to them in the first place, they are involved in a network, sometimes being fed and drained by vein-like structures, and thus in the process of changing and being changed by their network. It is a view of a self that is being produced in real time in proximity with other external beings and objects as well as the components of its own material/psychological makeup. When I’m focussing on borders it’s to point at the porosity in those borders rather than their integrity.

#

ÖÖÖ:

The paintings often depict archetypal characters such as monks, nuns, drunk men, chefs, police officers, construction workers, waiters, and Frankenstein. How do you choose these identities as sources of performative power or poetic metaphors in your artwork?

Justin Fitzpatrick:

There’s something about outfit and uniform in most of these figures, an identity that is put out visibly like a signpost into the world. I am interested in figures that are already symbolically quite loaded. Initially i was moving through homoerotic archetypes in pornography, ie, the construction worker, the police officer, the priest. At some stage it felt like i was just moving through the Village People line up. The relation between the erotic script and the social script is interesting, the symbols are very pluripotent, like stem cells, they can go in lots of different ways. A construction worker can talk about a kind of macho sexuality, or can be a communist symbol, whilst also talking about the physical act of construction, the creative process . Using such recognisable figures in my painting is a bit like cheating, i can import so much extra baggage for free into the narrative space, and it becomes creatively productive when i start composing them, playing with them like dolls, wherein the contexts i create around them modulate that symbolic weight they already have.

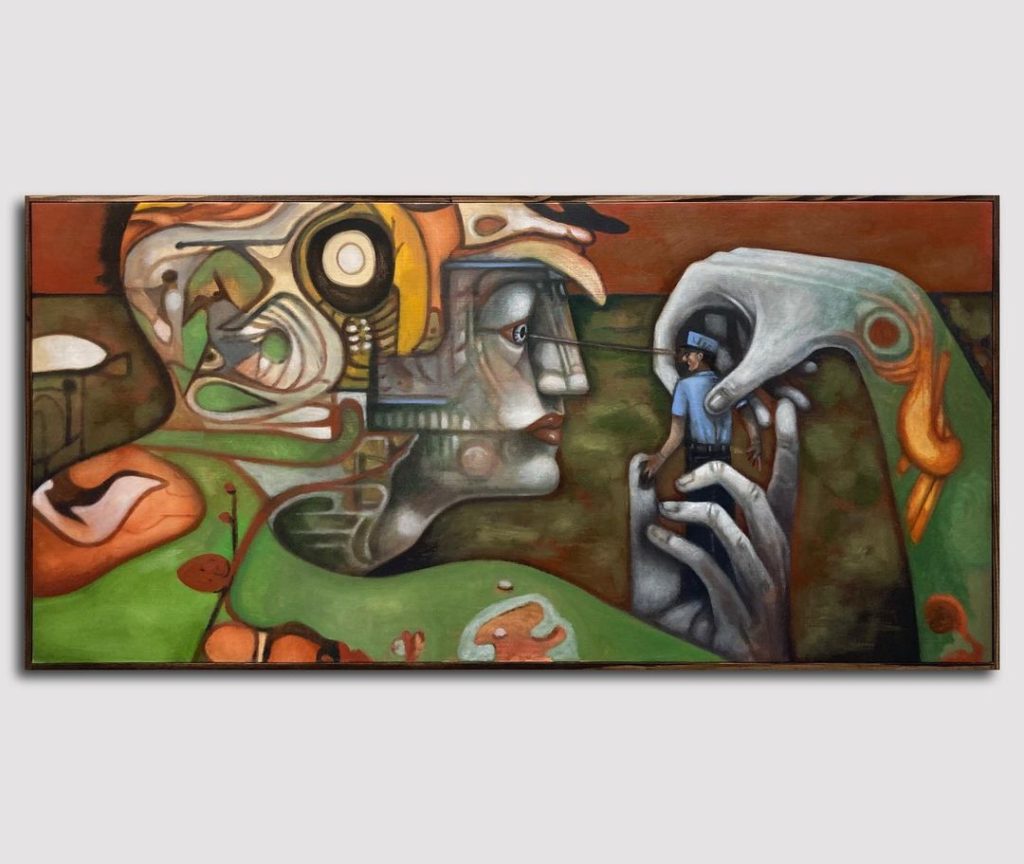

RIght:A Whisper in the Cloister, 2019

#

ÖÖÖ:

Exhibitions like ‘Angiosperm Telephone’ draw motifs from Denis Diderot’s philosophical dialogue D’Alembert’s Dream, while ‘Ballotta’ references the historical anecdote of Pergonal. Both explore consciousness and identity as the result of collective cellular interactions within a body. How do you seamlessly integrate these artistic creations with complex analogies from such references, as well as from metaphysical poetry and mythologies?

Justin Fitzpatrick:

To make work i need something to motivate me, i need a subject to cohere images and objects around. I have to find something that is a fuel for a show, that will give me energy, and an energy that can sustain me for the many months it takes to produce an exhibition. The Pergonal story was such an exciting one, of the origin of fertility medication coming from the urine of nuns, which would be turned into hormone replacement pills to be eaten by women struggling to conceive, a materialist mirroring of the body of Christ transubstantiated in the moment of communion.

Initially i tend to illustrate quite unoriginally the ideas in the text and it rarely works as a painting. It always feels a bit less than the original text or idea. I will then go into a stage of using these failed first paintings as surfaces to start experimenting formally on, and just get on with trying to make paintings that compel me, that satisfy me in another way. I get really lost in it and am often ending up at dead ends, I will basically try anything at this stage and there is a lot of non-logic that has to come in and infect the process here. It’s a stage where you’re asking the work to surprise you, and hoping that something exciting will emerge. At some stage in the paintings progress i find my way back to the subjects of my research and find places to insert their ideas into the compositions i have been improvising. There is usually a lot of disorder in the process. And if it goes well there is grace, and i feel like i have managed to talk about the subject while still engaging in the very particular and mysterious thing of making an artwork.

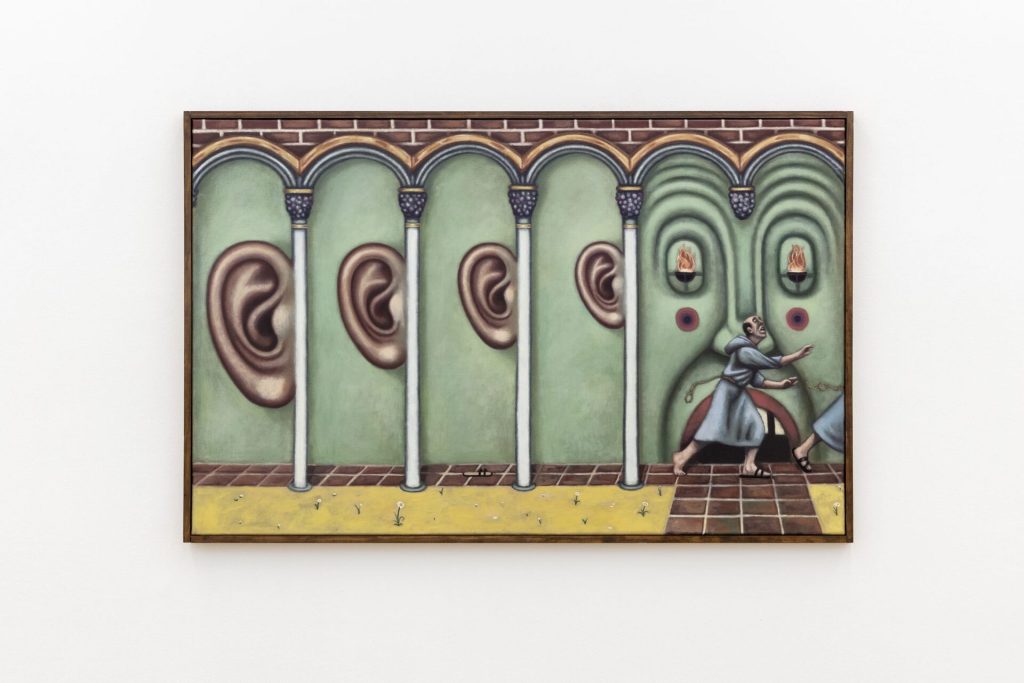

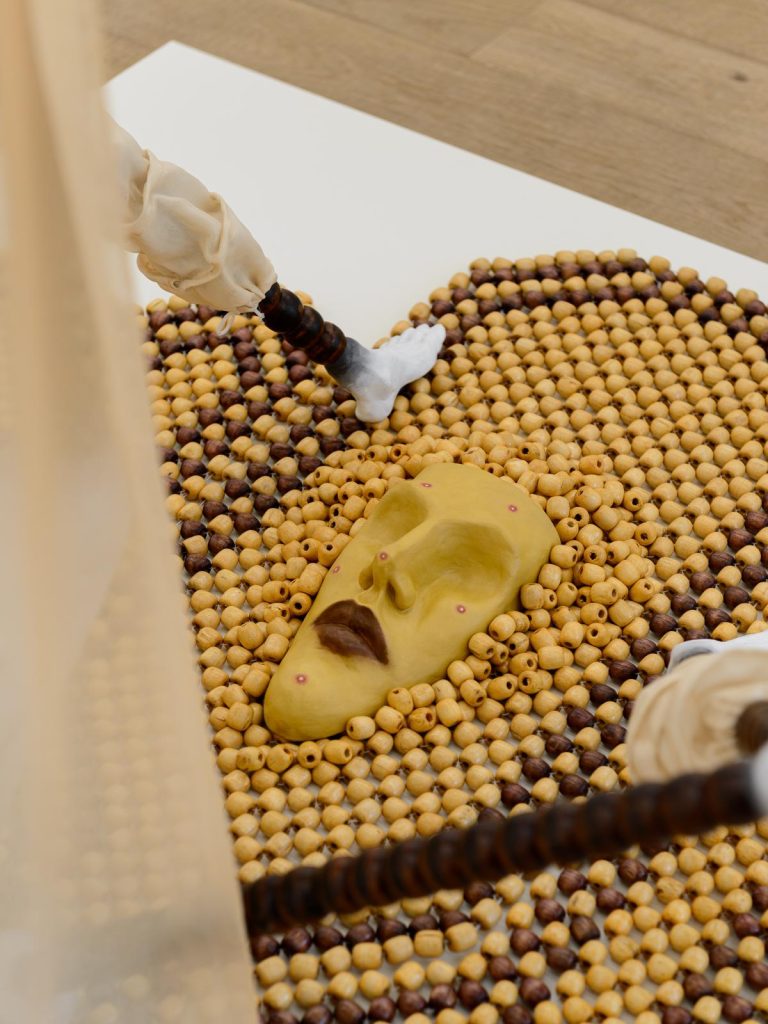

First row, left to right: Bee and pollen I, 2022; Histaminos,2022; Bee and pollen I, 2022 (Detail)

Second row: Perfume Is the Extension of a Body in Space, 2022

From Exhibition “Angiosperm Telephone”, Galerie Sultana, Paris(November 19 – January 21, 2022).

Photography by Gregory Copitet .

#

ÖÖÖ:

How did your early focus on queerness evolve into the current themes of biological disintegration and porous identity, and how do these themes connect to the interplay between human and non-human elements?

Justin Fitzpatrick:

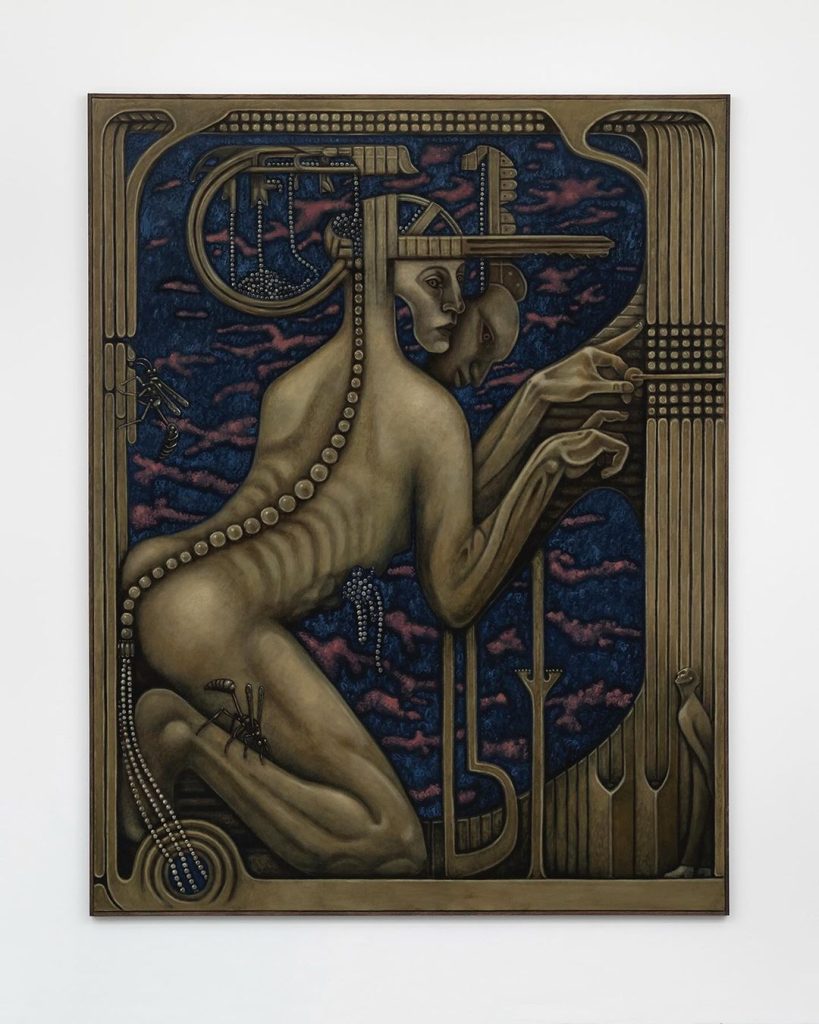

So much of the queer theory that i am interested in is focussed already on the porosity of identity, the capacity of transformation, the breaking down of fixed categories etc and so moving towards a more biological perspective felt very natural. I was reading texts by queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and they frequently reference Sylvan Tomkins’ Affect Theory. From this i started to look at the biological origins of affect, at people like Antonio Damasio, specifically his book ‘The strange order of things’ which discusses emotion as an emergent property of life related to homeostasis. It’s again the question of agency: where do these feelings come from, how can i account for them. It’s possible my interest in this subject might be a hangover from growing up gay, where a sense of difference causes you to address yourself in this register.

#

ÖÖÖ:

You’ve described writing as a ‘kind of machine to produce visuals for physical works,’ functioning in parallel with your visual art rather than merely annotating it. How do you start your writing practice in the context of art creation, and can you provide examples of works created primarily through this approach?

Moreover, do you see your artistic process as engaging with synesthesia as mainly as it appears in your art, and are there other inter-sensory connections you explore besides writing?

Justin Fitzpatrick:

Writing is useful to me because the way that writing makes you improvise is different from the way that painting makes you improvise.The way that your mind moves from one thought to the next when you’re making up a story can suggest something specific or absurd that you can then export into a painting. For the show Frontispiece, at Seventeen in London I wrote a text called ‘French Gardener’ which was describing a grand french garden with erotic-themed fountains that acted as a giant logic gate, a computer powered by water instead of electricity. The paintings in the show didn’t address this fountain at all, but I took smaller visual cues from the text and they produced starting points for paintings so it felt like a cumulative world was being built, that it could keep growing outwards.

In terms of synaesthesia, I’ve never had the experience of smelling colours or tasting music in the literal sense that other people describe. I am however interested in the way the different world that each sense creates intersect and compare to each other, and how I can evoke the specificities of these. The way an eye samples the world, and the way a nose samples the world, the type of affective response they create, how a smell can move you backwards in time to a memory. I like to address the overlaying of all of these worlds, how we have so much sensory apparatus stacked together in a little box at the top of our body.

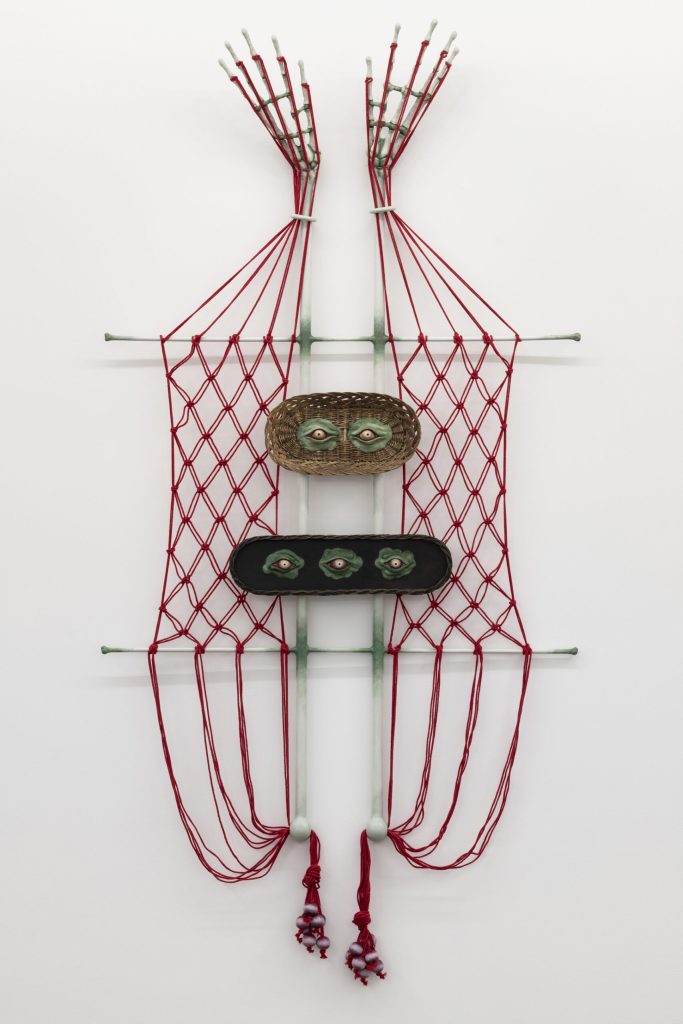

Right: Flexor Bread-basket, 2020. Photography by Damien Griffiths. Courtesy of the artist and Seventeen, London.

#

ÖÖÖ:

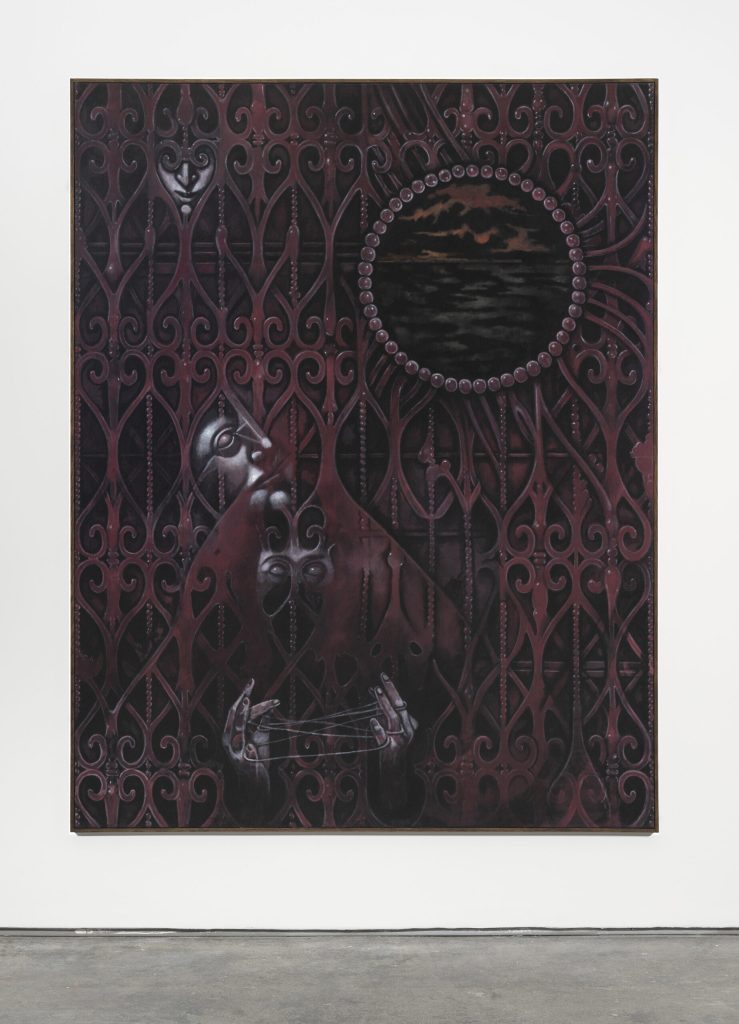

Why did you choose the illustration style combining Art Nouveau and Gothic elements as your main form of expression?

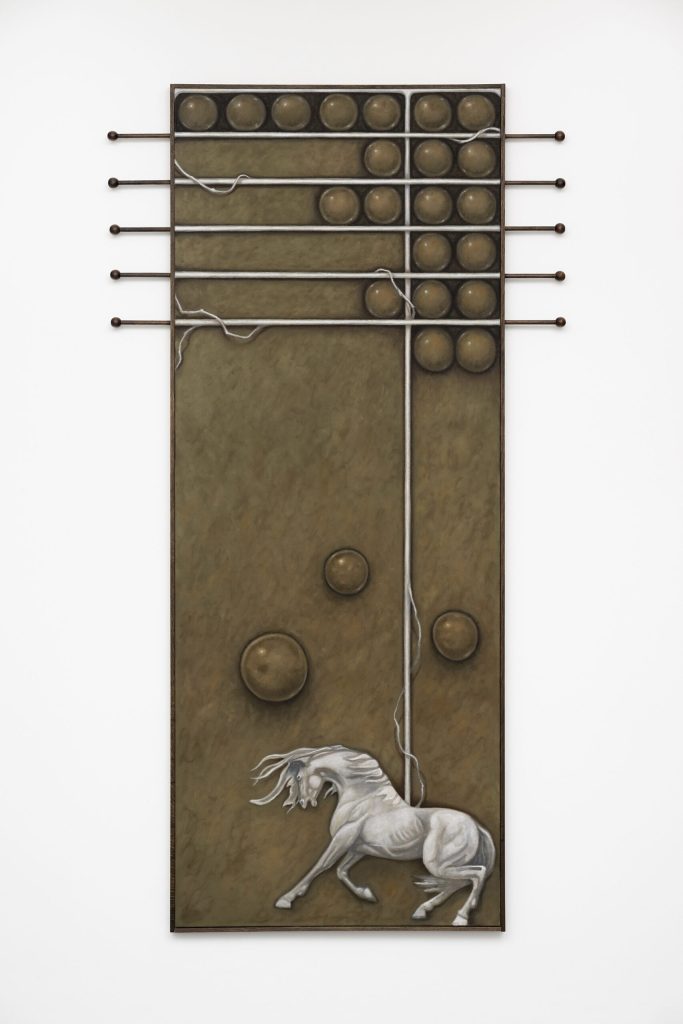

Middle:Thynnine Wasp Pheromones, 2023 (Middle)

Right: Monnaie Vivante (Citric Acid Cycle), 2023

Justin Fitzpatrick:

Art nouveau interested me for a number of reasons. It is a visual style which is very interested in the network or system, everything is twisting and turning around itself like Celtic knotwork. People criticised art nouveau because of its gaudiness, its lack of function, which is maybe fair, but I am fascinated by ornament. In the natural world ornament and function are indistinct. A plant is rooted in place so it must draw the pollinator towards it by means of its ornamental structures, its flowers, its volatile compounds of perfume. The elegant twisting vines of a climbing plant are the plants attempts to understand its environment and support itself. Inside our bodies we have the nervous system or circulatory system: Art Nouveau drawings of the body inscribed within itself. As for the gothic, its a mood i am strongly drawn to in the culture i consume. I think gothic literature is very concerned with the affective qualities of space, of architecture, which is often haunted by human emotion. Also it seems to be about the things held under the surface of a person or personality which in their hiding produce an energy which explodes into feeling when they are released.

#

ÖÖÖ:

You’ve shared appreciating works by artists such as Max Ernst (‘Garden Aeroplane Trap’), Ernst Fuchs (‘Battle of the Metamorphosed Gods,’ ‘Head of a Cherub’), Hans Bellmer (‘Les Mains Immobiles’), and Thomas Theodor Heine (‘Angel’).

Could you discuss how any of these pieces, or others, have profoundly influenced you?

Justin Fitzpatrick:

I think one of the pieces that has most affected me, or has been useful in my recent thinking is a fresco sequence by Piero Della Francesca, called ‘The legend of the true cross’ in the Basilica San Francesco in Arrezzo, Italy. The sequence of frescos follows the wood that formed the crucifix from its origins as a seed from the tree in the garden of Eden to the death of Jesus, the wood being present at numerous important ‘historical’ moments. The story feels like a Philip K Dick story: an object that attracts important historical events to itself throughout time, spending years buried under the earth (having been buried by King Solomon) and then calling out, somehow being found and dug up again to take part in another historical event. There is something idiosyncratic about a narrative spanning centuries being witnessed by a piece of wood which i enjoy greatly.

#

ÖÖÖ:

Finally, could you recommend a book or piece of music you’ve been enjoying recently? Thank you!

Justin Fitzpatrick:The book I spent all last year reading and re-reading was ‘Power, Sex, Suicide’ by Nick Lane. The title sounds quite salacious, but it is concerned with mitochondria, the organelles inside of every cell in our body that are genetically distinct from our nuclear DNA. The title refers to the fact that they power the cell, that they are responsible for the evolutionary development of sex, and that they are responsible for the programmed suicide that allows cells to function together in a multicellular organism like ourselves. It’s a really fascinating book, i highly recommend!

And thank you for your questions!

Artist Info

Justin Fitzpatrick

ÖÖÖ is growing in primitive future.