Ö10 Artist: Eliška Konečná

Interviewed by Yuän (ÖÖÖ)

#

ÖÖÖ:

There’s a meditative and dreamlike quality to your work. The soft, velvet textures of your textile materials conjure sensations of home, intimacy, sleep, and dreams, reaching into the emotional subconscious and touching on a vast sea of universal, collective memories. Furthermore, the physical form of the bas-reliefs seems to become a body itself that feels tangible and reliable, existing within the human bodies you portray. What drew you to working with fabric, and how do you feel the medium influences or transforms the stories you aim to tell?

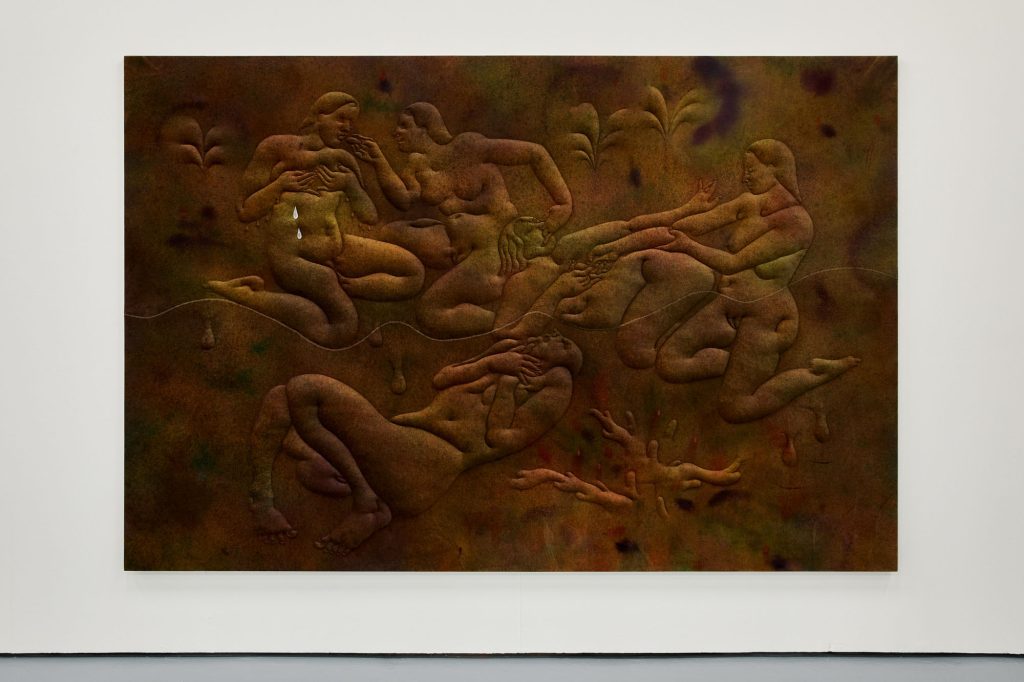

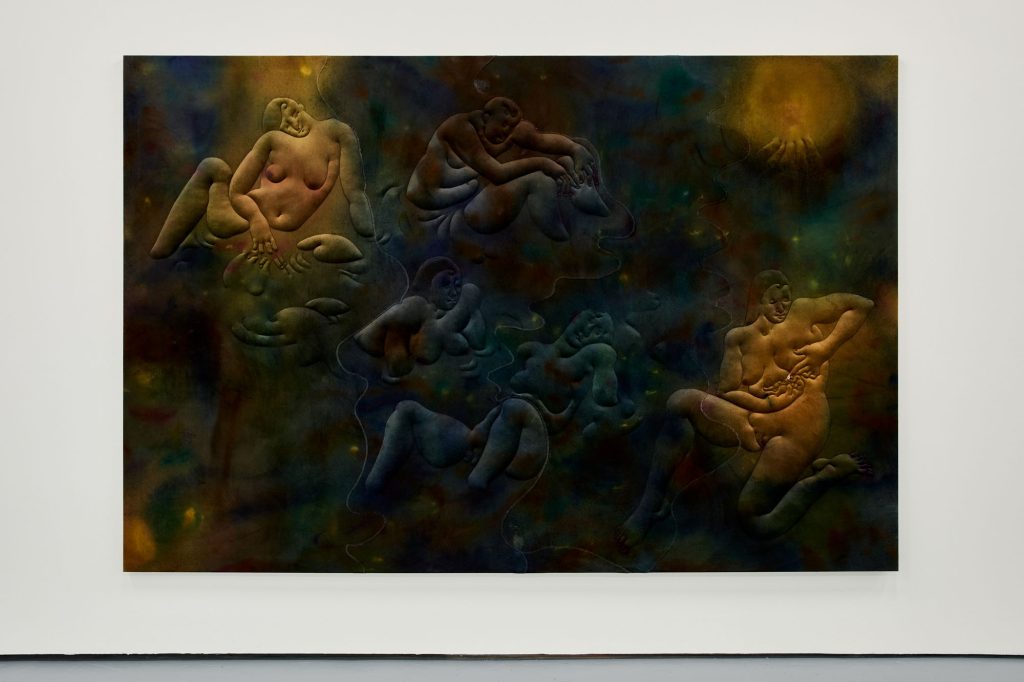

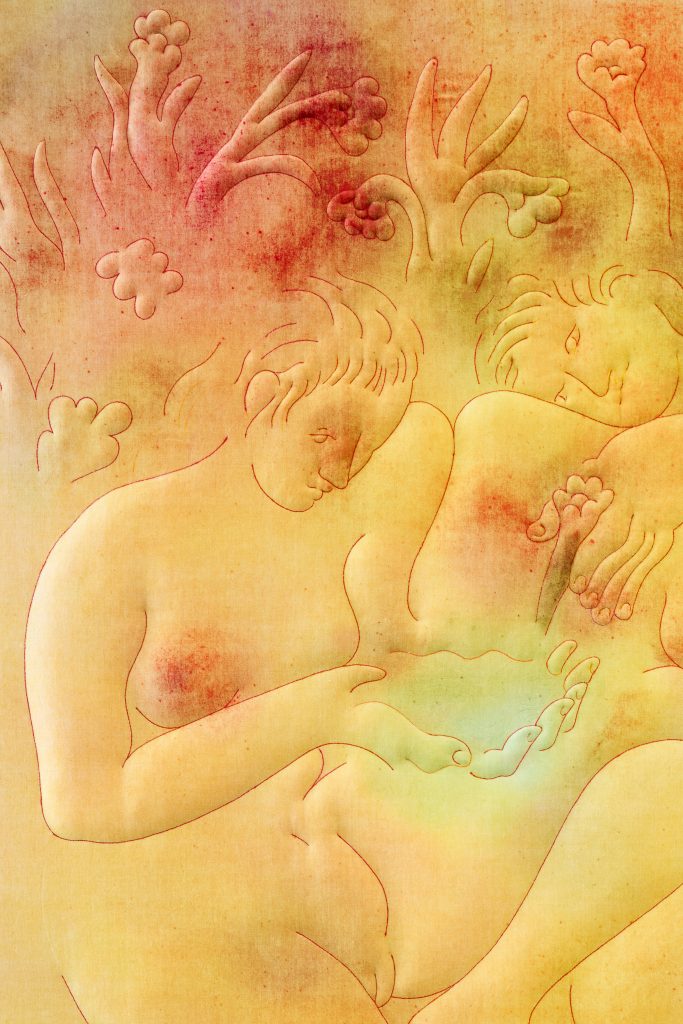

Wildflowers Treating, 2024

Photography by Jan Kolský; Courtesy of the artist and Polansky, Prague

Eliška Konečná:

For me, the choice of media represents a highly essential element of my work. In this respect I approach it in the same way as language – I consider every medium a tool that allows me to express myself properly, in the same way that a person chooses words during an interview. A conversation between two people is in its essence also a form of art, especially if we aspire to understand each other and make an effort to do so. That’s also the level of attention with which I approach selecting the technique I employ in my work.

Back when I made the shift to using textiles, I was studying painting. And unfortunately, even though I am trying to overcome it, I have a tendency to simplify things into antitheses. I perceived painting as a medium that was either descriptive, when I simply left the observer to a passively take in a clearly defined painting, or as an abstract medium, when on the contrary the painting exists beyond my control a I do not have the possibility of influencing how it will be perceived. I found neither of these approaches satisfactory, however. I needed to find a medium that would enable me to work with an artwork within the context of common experience and emotions.

At the time, I began embroidering for the first time, I wanted to employ embroidery and infilling to – figuratively speaking – write something into the painting. Back then they weren’t letters or words as such, I created maps which were a continuation of my residency in Hollland where I think I got quite close to the phenomenon of Hikikomori and thus created a very intense relationship with the space of a room that I basically almost never left. I originally wanted to paint on canvas that I had padded out and stretched in this way, but the resultant effect of the embroidery itself fascinated me. A map is a depiction of lines, a carrier of information, but in my bas-reliefs the lines would disappear beneath the substance of the emptiness that that surrounded them. What is on the map is secondary, it is where there is nothing – an absence – that becomes the essence.

It didn’t take long, and it became apparent that I’m an obstinate figural artist. But the principles for which this medium made sense for me at the beginning have also become manifest on the more poetic level of expressing what it means to be truly human.

This technique has two key aspects for me. The first is that the resultant bas-relief is two-sided – one side mirrors the other, which means that it’s the same, and at the same time different. The second, even more important attribute lies in the fact that where one body is located, there is no longer space for another. When one figure reaches for something over another, it actually divides it. If the figure penetrates too deeply into the silhouette of the other’s body, it literally enters into it. On the contrary, when one figure touches only the edge of the other, it defines not only the other body, but also itself.

#

ÖÖÖ:

When we first connected in 2020, your creations illustrated intimate bonds between souls through gender-neutral human figures. In your more recent pieces, we witness the portrayal of female figures in their natural states, radiating harmony and vitality while embodying timeless archetypes of femininity and motherhood. These figures seem to inhabit an ancient, untouched world, evoking images of a primal landscape or a myth-like paradise. Can you share what drove you to explore these particular themes, from your earlier works to those of today?

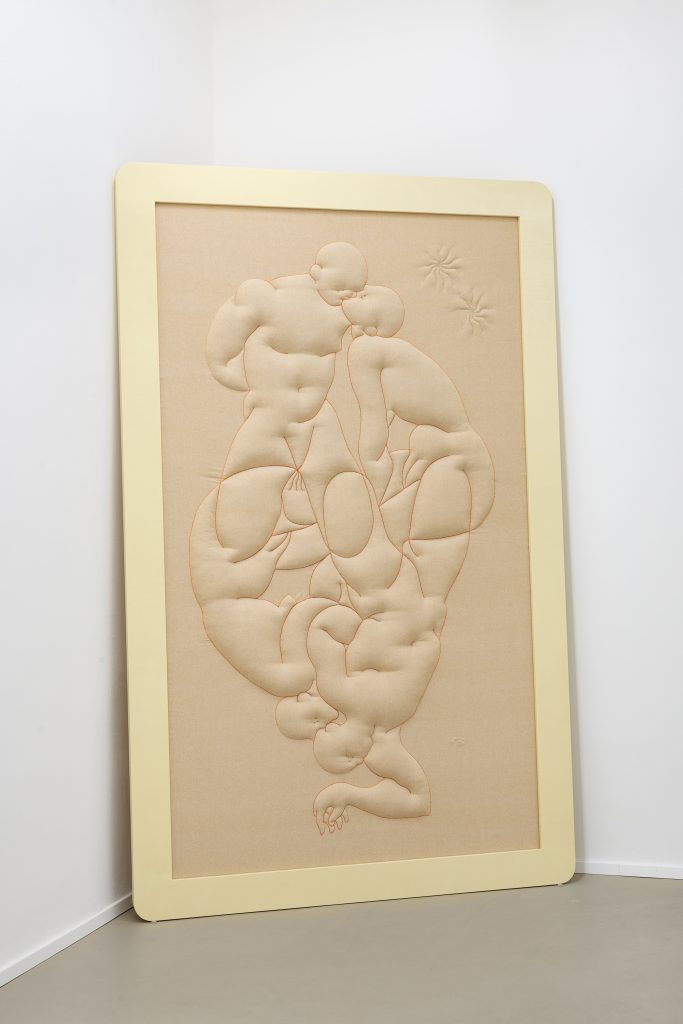

Antagonism of Me and You, Diploma installation set, 2020

Eliška Konečná:

Perhaps back then it wasn’t clear that I was assigning gender to my figures, but I was. Then the figures became women. I perceive my own female body as a reference for any other body, it is the only experience of existence that I have. I decided to portray the human being purged of the roles that would influence the way viewers perceive the artwork. I was interested in the dynamic of the situation between two people, without their gender roles bringing in another, different, meaning, as would be the case if I placed women and men into the same situations.

Over the last few months, however, I’m getting the feeling that my approach has changed, and I’m returning to the question of gender division with an even greater intensity. Previously I worked with the inclination not to divide, I looked for neutrality and universality, I freed my work from prejudices and roles. Paradoxically, thanks to this exploration of neutrality I came back to a basic realisation – the thought that differences are not only unavoidable, but fundamental. This journey took me to a deeper investigation of these differences, rather than avoiding them.

This turn came about a while ago when I was working on several small models for larger executions of wooden sculptures. I was personifying desire and so arose the idea of Desiré. Only later did I realise that even though I am a woman, I was thinking through the eyes of a man – in other words I was interpreting the subject, or rather portraying it, as a fallen woman, even though my intention was to elevate the subject’s authenticity and in particular the legitimacy of its desires.

It could be us, 2021

That’s when I started to devote attention to the Biblical story of the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden and started thinking about Eve and the act of plucking fruit from the tree of knowledge which I considered to be a courageous rather than a sinful act. Shortly after that I realised that this thought had already been articulated, primarily within feminist theology.

With these ideas in mind, I am at the moment working on a series of small-format works entitled Study of Sin. It’s a loose continuation of the work Study of Touch and Vessels from 2022. Here I am focusing on hands and their interaction with a plucked fruit: they are squeezing it in order to give a drink of its juices to a scorpion perching in the other hand, they are tearing it apart to extract the stone, offering the fruit to other hands so that they can briefly touch it or clutching an already plucked apple. I’m concerned with placing the so-called original sin in various contexts, thus casting doubt on its sinfulness.

Primarily, though, I am currently focusing on a new set of work for my upcoming exhibition in 2025 in Milano’s eastcontemporary gallery. This series works with a similar theme but is not so directly tied to the figure of Eve; it is more focused on the original figure of Desire. In the work I examine what is a priori perceived as fragile and weak or is considered to be a symbol of fragility or decline and I try to reinterpret this and offer a different definition of strength and dominance.

Monologue, 2021

Courtesy of the artist and eastcontemporary, Milan

#

ÖÖÖ:

We also see series like Study of Touch and Vessels, which explore hands in tactile interactions with objects. Having experienced motherhood and nurturing life, how do your personal experiences influence this blending of the familiar and the surreal in your art? Are there specific feelings you aim to capture?

Study of Touch and Vessels, 2022

Courtesy of the artist and eastcontemporary, Milan

Eliška Konečná:

I was trying to realistically portray hands and the way they touched vessels that were actually not present in the picture but appeared to the observer only thanks to inferring the ellipses in relation to the specific flexing and attachment of the palms of the hands. At the time I thought very intensively about the verbalisation of experience and an idea came to my head about how to describe a glass vessel holding water to someone who had never seen glass. At the same time, I also had in mind Heidegger’s concept of vessels (“Krug” – the jug) with respect to the question of being and things. He describes the way that we should understand objects. Not merely as objects, but entities that link us to the world. He explains that the true essence of a vessel consists of its “emptiness”, that thanks to this attribute it can serve its purpose. I’m not sure if I understand it correctly but somehow it captivated me already a long time ago. And back then it made sense to me to devote myself to it, but I am not aware of a connection with my physical condition at the time, in other words my pregnancy, and when it occurs to me, it seems too banal to be real.

#

ÖÖÖ:

“Eliška Konečná’s works are an ode to sensuality. Bare, timeless, universal sensuality. Her characters, such as antique gods, often give in to temptation, leading them to unavoidable mistakes. Their bodies exist both as the manifestation of their desire and the vessel of their punishment. Bodies with basic needs struggling with their souls and their morality issues. It is a mythology we feel already familiar with. Too familiar in fact, to experience any empathy towards its characters. We observe them as we meditate in dreams, seeing ourselves in every character, waiting to see how it ends, because we might learn what we have to fear. ” (Text by Caroline Krzyszton)

There have been reviews that often draw parallels between your work and ancient deities, or view it as developing its own mythological narrative. How do you see your creation as engaging more with mythology or being rooted in realistic, earthly experiences?

#

Eliška Konečná:

It’s a little presumptuous, but the way I understand these parallels is that if Mythology serves to provide people with answers to the basic questions about existence, morality, desire, death and life, my work could – from the viewpoint of those specific writers – have a similar ambition.

Of course, the goal of fine art is not to offer answers, but rather to pose questions. But even questions have their roots – in a similar way as mythology and ancient legends – in realistic, earthly experiences. To me this interconnection seems natural, rather than exclusive.

Caroline Krzyston who used these parallels wrote texts for two of my solo shows and I could easily consider them to be my own artistic manifestos.

I’d rather not associate my work with ancient legends and mythology because it’s well-known and as a term has perhaps become empty. But if I try not to be too much of a stickler about it for the sake of my own inner peace, I have to agree with it, especially when this expression makes sense within the context of Caroline’s words.

Personally, I don’t describe my process that way, though, I say to myself that I’m trying to examine and portray that which isn’t present in the physical world, but is aroused by it and materialises in our personal mental space. And I then explore this experience through its physical materialisation.

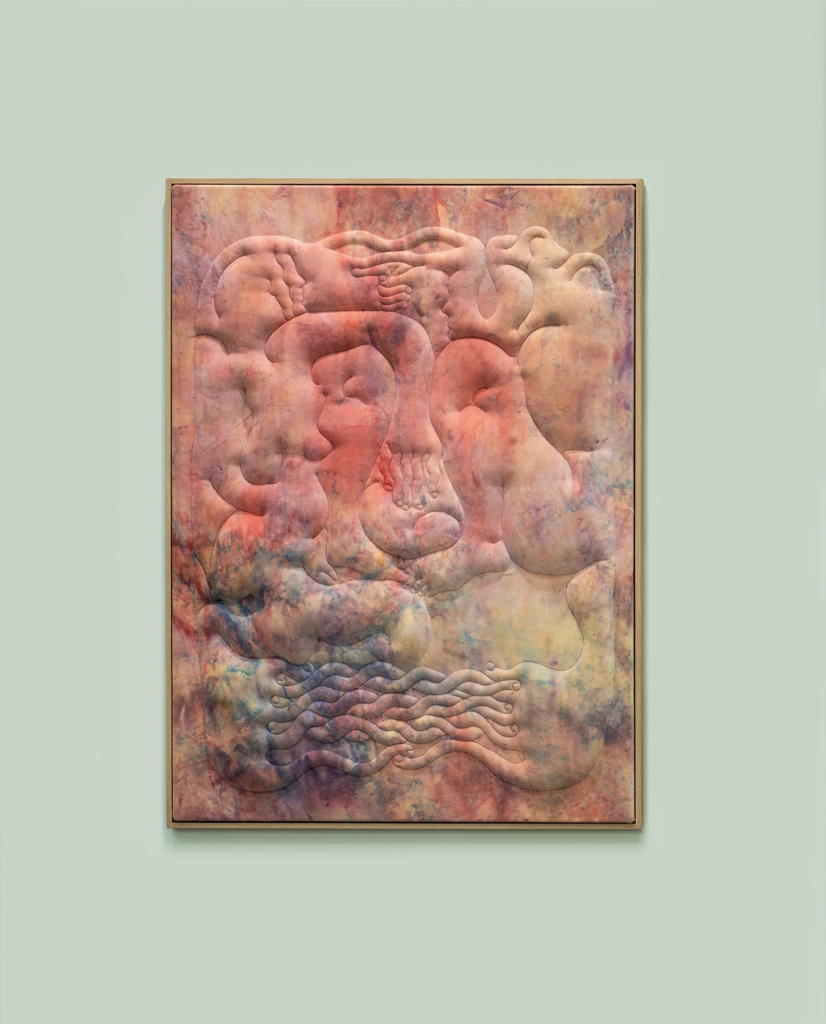

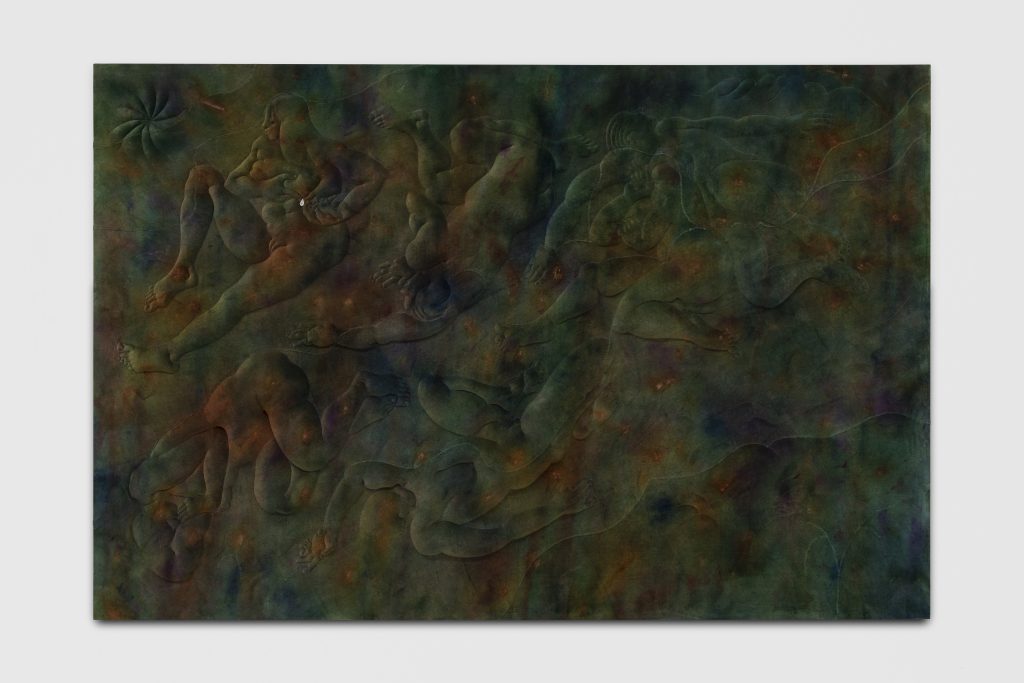

Looking for a Dry Place to Fall, 2023

Pus is Honey now, 2023

A Jar full of words, 2023

Courtesy of the artist and eastcontemporary, Milan

ÖÖÖ:

The triptych Thirst, featuring The Great Feast, The Great Bath, and The Great Sleep, the scenes showcased fundamental human activities—eating, bathing, and sleeping. In these moments of simplicity, humans are no longer separate but rather united with nature’s life force, as if their essence joins that of plants, animals, and other living entities in a harmonious flow. How do these scenes resonate with any philosophical perspectives they may embody?

Eliška Konečná:

If we look at the triptych Thirst, I was not only concerned with investigating basic human needs – food, bathing and sleep – but also with questioning the simple notion that these activities automatically symbolise harmony with nature. In practice I was actually trying to cast doubt on the idea that at these moments the human being, interconnected with nature, is somehow ideally integrated with the surrounding world and other beings. Instead, I concentrated on the ambivalence of these activities and their potentially negative impacts, which are often linked with our understanding of care and power. In this sense I wanted to show that even simple activities conceal the tension between good and evil, between what is considered a positive act and its actual consequences; and vice versa.

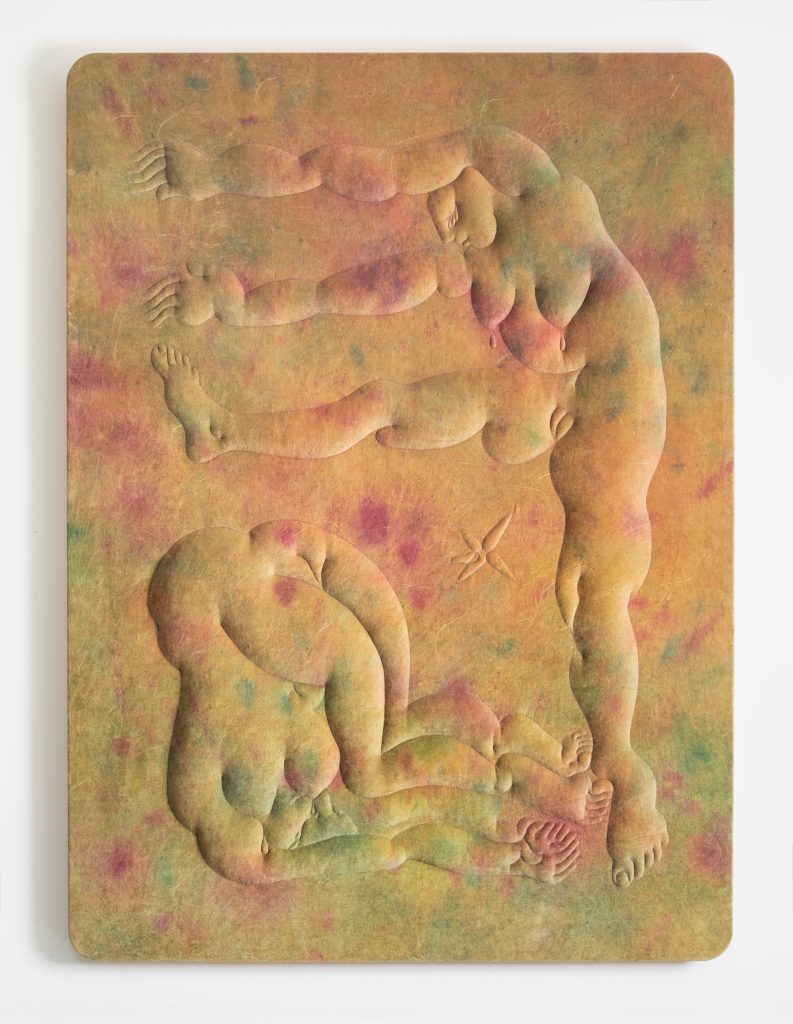

The Great Sleep, 2023

#

ÖÖÖ:

In The Great Sleep, a mother is seen offering her milk to what appears to be an abandoned or dying bird. Does this action reveal a nuanced facet of motherhood and maternal instinct, even potentially introducing a subtle tragic undertone?

Eliška Konečná:

The bird that the woman is feeding with milk is an interesting symbol of ambivalence, for me. A bird is not a mammal – milk will not help it and nurturing thus becomes a kind of gesture on the boundary between caring and blind imposition. This work illustrates that even something that appears to be an act of aid can in its essence not only be ineffective, but in fact harmful. That brings back the question whether caring itself – maternal, female or simply human in general – always brings good. The breast thus becomes a symbol that casts doubt on the traditional notions of female gentleness and maternal care. In the triptych I wanted to show it in the cases of two different atmospheres: on the one hand there is the indifferent crowd of sleeping people (The Great Sleep ), on the other the inquisitive, almost uneasy onlooking of the others (The Great Bath ). The central painting (The Great Feast ) then crowns this ambivalence with a cyclical narrative about caring and rejection. For me it’s important to think about a woman not only as inherently good, but also a complex being that can be a bearer of power just as much as a man – and that power can be creative as well as destructive.

(In both wings of the triptych the breast in fact appears as a new symbol of the phallus. Just like the phallus it symbolises the patriarchy with which domination and power are connected; here the breast indicates that the female principle is not naturally “good” or innocent. The woman, although she is also often perceived as the opposite of man and thus as creating the antithesis of the patriarchy, can carry a similar ambivalence of power within her).

#

ÖÖÖ:

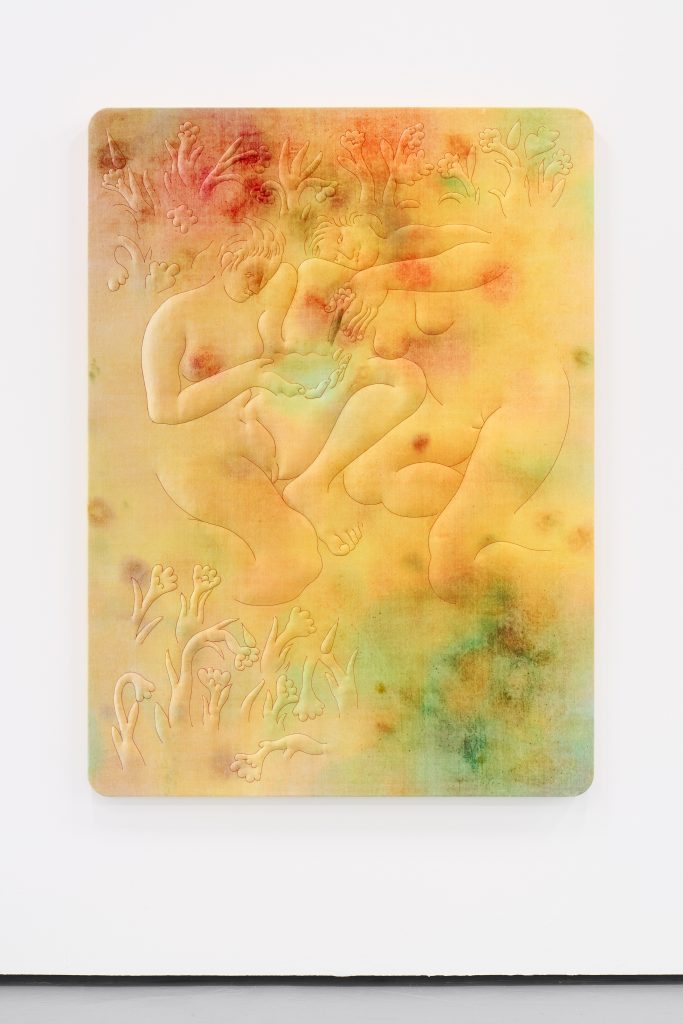

Water and flowers are recurring motifs in your work. What captivates you about these elements?

Fountaine, 2023

Photography by Jan Kolský; Courtesy of the artist and Polansky, Prague

Eliška Konečná:

The motif of water has been appearing in my work since I made my first figurative bas-reliefs, at the time I was looking at the phenomenon of Folie à duex which is a psychiatric disorder occurring at the same time in two people who are in close contact. This specific bas-relief portrays two human beings and a dog, whose silhouettes were filled in with ripples, as a very banal symbolisation of water. While the dog and reclining figure were entirely “below the surface”, the sitting figure could still keep at least its head above water.

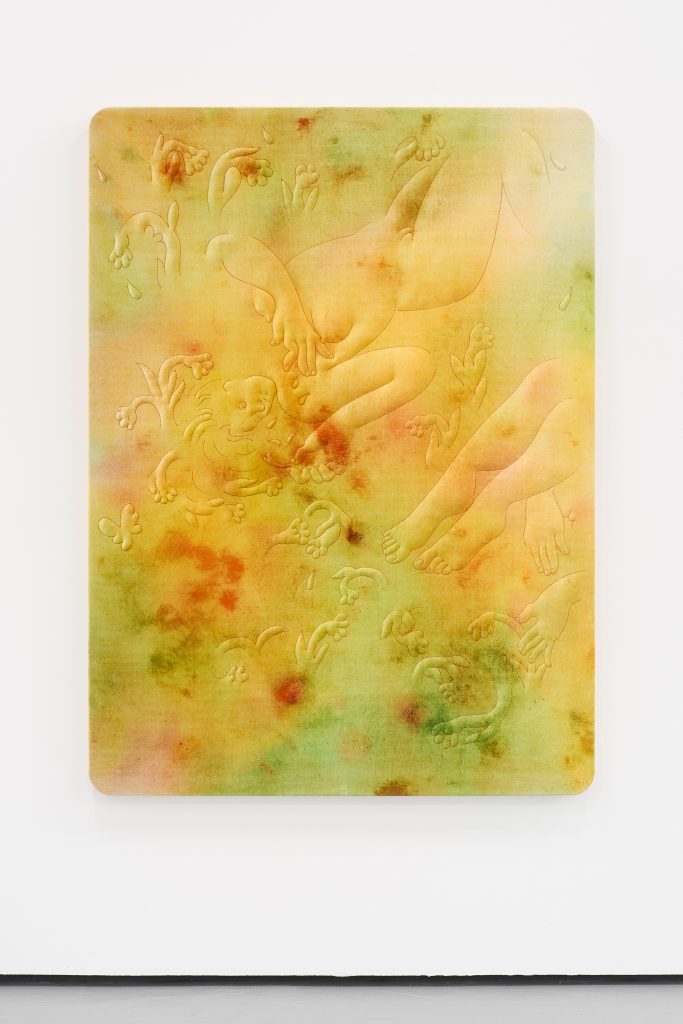

I think that water as a body of matter, a mass, is for me a symbol of some form of boundary, screen and barrier, which although it is permeable, it is still present; whereas liquid in the form of a drop is for me personally a symbol of a word, speech and language. Without context, the silhouette of a drop conveys no meaning, it has the potential to mean anything, but when we witness where it is coming from and what it is – a tear, blood, milk, honey or seed – only then does it get narrative meaning.

Flowers on the other hand have only appeared in my work recently, they started to interest me more when I was focusing my attention on Czech folklore where flowers play a major role. For example, as little girls we used to tear petals off flowers – going down in sequence, each odd leaf meant “he loves me” while an even leaf meant “he loves me not” and that’s how we asked torn out flowers about the feelings of those we loved; the revelation came with the finL petal. And that fascinates me in some way. Tearing flowers out of love. It seems paradoxical to me but not harmful in any way, of course. Just paradoxical, and it’s in my nature that these kinds of little contradictions interest me. The fact is that they are analogical to the greater and more essential paradoxes of human behaviour.

And last but not least, the petal has the same silhouette as a drop of liquid, and when it falls on a face on an artwork, it becomes a tear, etc.

In the end we also pluck flowers in the name of love, 2024 / Noontime in July, 2024

Photography by Jan Kolský; Courtesy of the artist and Polansky, Prague

#

ÖÖÖ:

In your artwork, there’s a sense of returning to one’s origins, recalling feelings of belonging. What meanings do “belonging” and “home” hold for you?

Eliška Konečná:

For me, home entails some personal, intimate experience with oneself, and thus it’s a feeling that’s fairly easily achievable for me. Belonging on the other hand, in other words an experience connected to another individual or community, is a much rarer emotion for me, and I think that’s why it’s one of my essential themes.

#

ÖÖÖ:

What’s been your favourite book or music lately that you’d like to share with us?

Thank you!

Eliška Konečná:

The book I’d like to recommend is one I read already a while ago, but should read again, and that is Patters of Culture by Ruth Benedict. It’s an important cultural anthropology. I also can’t omit to mention Louise Glück’s poetry collection The Wild Iris.

As far as music goes, right now, as in the past, the song that still does it for me is Eden by Hooverphonic from 1998.

Thank You Yuan!

Artist Info

Eliška Konečná

ÖÖÖ is growing in primitive future.